5 Things You Need to Know: Rent Control Goes National and the Labor Department's Fuzzy Math

Let's get back to the issues after a crazy news cycle

To learn about the origins of Five Things, scroll to the bottom of this piece.

1) Cutting through the noise

In a week where insane political drama dominated the news cycle, it seems almost trivial to talk about real estate.

Interest rates, apartment deliveries, retail foot traffic, Realtor commissions - it all appears so insignificant.

But that's exactly what we should be talking about.

What they used to call "the issues."

Which have been lost sadly, swapped out for televised theatrics, staged shenanigans, and toxic political discourse designed to keep us talking about everything BUT the issues.

So let's not let them win.

Let's not devolve into the partisan tribes they want us to separate into.

Instead, let's come together around universal truths on which the left, right and center can agree.

Like the fact that cap rate is a meaningless metric that can be juiced be pushing repairs "below the line" on the T12 to convince a trade buyer that the broker's numbers are, in fact, true.

And that championing rent control for political expediency should be resisted, because whatever the good intentions and marginal benefits of these policies may be, the downside will win out in the end.

2) Rent Control Goes National

Before being railroaded out of our feeds last week by juicier political storylines, President Biden floated the idea that if reelected, he'd implement 5% rent control nationwide.

Which kind of caught everyone off guard because, what?

(For a deep dive into San Francisco rent control, check out my piece from last week)

Short on details of how the policy would be implemented, Biden suggested that large property owners could lose tax breaks if they get caught raising residential rents by more than 5% per year.

The takeaway here is not that this is viable policy, since rent regulations live at the state and local levels, but indicative of how mainstream the "housing crisis" has gone.

Housing seems to be too expensive, everywhere.

In fact, and remarkably close to the seemingly random policy announcement, a recent survey found that 91% of Gen Z’ers chose housing affordability as their most pressing political issue.

Setting aside for a moment that the survey was commissioned by real estate brokerage RedFin (see #5) , it is telling that housing affordability ranked 20 points higher than "preserving democracy."

But enough about politics already.

3) Speaking of politics

Apparently there has been some news surrounding the top of the big presidential tickets over the past couple weeks, but we're just going to close that tab and check back in in a few weeks (months).

4) But while we’re at it

This one is government-adjacent and has been eating at me for a while.

Every month, the US Department of Labor calls a bunch of random Americans, asks people who have time to chat with a government telemarketer in the middle of a weekday about their employment situation, then use the data gleaned from those calls to generate the most important economic report for the most important economy in the world.

Meanwhile, dozens of highly paid, highly trained teams of economics sharpen their pencils and try to project what the Labor Department will report every month.

And none of them seem to get it right.

Most are within the ballpark, but some estimates are wildly wrong, which has made me wonder whether these macroeconomic models are so very different, or if the Labor folks are so opaque about their methods that hundreds of professional economists cannot figure out what data they're actually looking at each month.

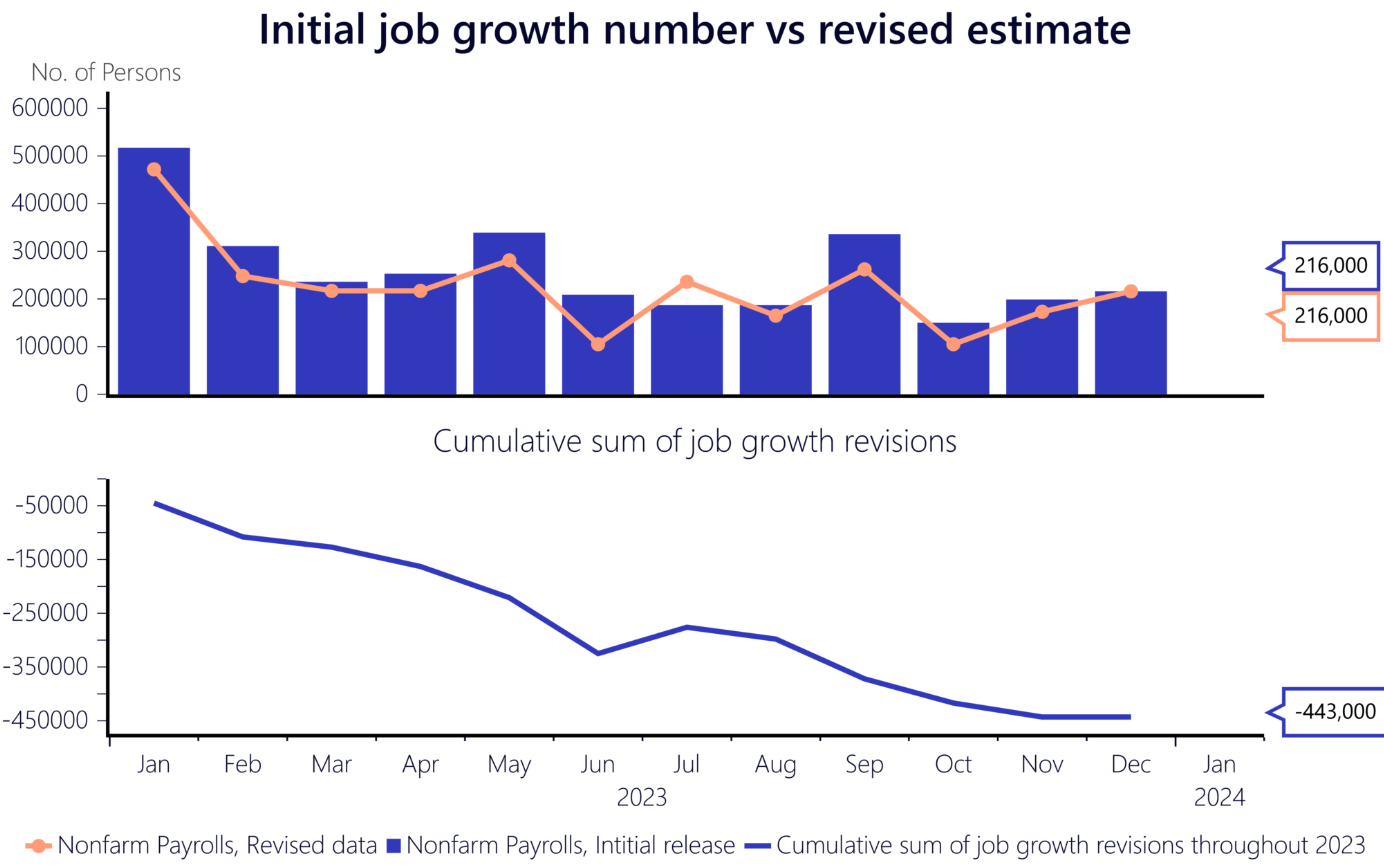

For example, in January 2023, economists expected the US economy to add 187,000 jobs. When the jobs report came out, it showed a whopping 516,000 new net new jobs created. Which is almost 300% higher than expected.

There are a bunch of explanations for this, from seasonality to surprise events to reporting changes. None of which are compelling.

The only explanation I’ve found that holds water is the numbers are hard to predict on purpose.

The Labor Department issues revised numbers months after the original ones, and the majority of those revisions recently have been negative, meaning the original report overstated the employment picture.

This is common during recessions - and not entirely reassuring given who stands to lose when economies go sour.

So maybe we should give those economists a break for handling dirty data (nah).

5) Sorry, did you say dirty data?

Well, obviously.

As the saying goes "lies, damn lies, and dirty data."

Anyone with experience crunching numbers knows that virtually every data set needs to be "cleaned up" before being useful.

And often this cleaning takes not only more time than the analysis itself, but can be trickier and more impactful on the results, since observations are removed during clean up are never seen again.

Cleaning is a total valid part of the process, since data sets often contain outliers and honest errors which could corrupt the analysis if left in.

But its an art to know what to take out, what to go back and doublecheck, and what to leave in. It’s subjective, making the statistics more of an art than its practitioners would like to admit.

It takes time and subject matter expertise to clean data properly, since how do you teach a first year excel monkey at Moody's to take out data if "it looks dirty."

So it quickly becomes obvious why the bad things that they say about statistics are mostly true, that data is easily massaged to fit whatever story the person handling the data wants to tell.

And as I write this, it slowly becomes clear why economists are so lousy predicting employment metrics that reflect back on the job that the administration publishing the data is doing.

—

The Story of “Five Things You Need to Know”

During a stint at Minyanville, a financial news and education media company, I was fortunate to work under the tutelage of a talented editor named Kevin Depew. Depew is now the deputy chief economist at consulting firm RSM, and wrote prolifically during the Great Financial Crisis, brilliantly capturing the mood of America during that trying time.

Depew’s "Five Things You Need to Know" was required reading every week for thousands across Wall Street and even down to DC, and covered topics from high finance to macroeconomics to social trends. This series is an homage to Kevin, who patiently mentored me and often quipped "I majored in philosophy, but since none of the big philosophy firms were hiring, I went into finance."