It's Time to Evict Prop 13

A property tax overhaul is the only way to unlock the housing California sorely needs

California’s housing affordability crisis didn’t happen by accident: It was engineered.

For nearly five decades, the Prop 13 property tax regime has deepened the state’s social schism, pitting the young versus the old, rich versus poor, capital versus labor.

By sabotaging the state’s ability to fund and build new housing, Prop 13 is the quiet engine behind a broken housing market, which voters rank, year after year, as the state’s most urgent challenge.

Yet it endures, propped up by an unlikely alliance: affordable housing advocates and real estate interests, both clinging to the same perk — ultra-low property taxes.

It doesn’t have to be this way: There is a path to wiping Prop 13 off the books.

But the road is hard, guarded by a consortium that for decades has successfully defended the Prop 13 regime for the benefit of long-term residents at the expense of newcomers and families scrambling up the social ladder.

Meanwhile, the law’s impact on the high cost of housing in California has largely escaped scrutiny, since pro-housing folks typically aim their ire at NIMBYs, restrictive zoning and gatekeeping organizations like the California Coastal Commission.

This is why any serious attempt to fix the Prop 13 problem in California must at its core be a housing initiative. Because otherwise we’re just talking about juggling money from one pocket to another, hopelessly waging into unwinnable war over “fairness.”

In this piece, I present an actual alternative to Prop 13 – a full-fledged repeal and replace of the most damaging legislation in the state’s history.

Wiping away Prop 13 is an essential step on the path for California to once again become a land of opportunity for the many rather than a bastion for the few.

This is a battle worth fighting, because the future of California is at stake.

Rip Off the Bandaid

This proposal is the output of research into Prop 13’s history, why reform efforts have repeatedly come up short, and my own experience witnessing how the Prop 13 property tax regime distorts housing markets.

Below I present a viable alternative to Prop 13, underscored by five core principles:

1) This is a housing-first proposal, and I do not shy away from that.

2) Adverse effects on specific groups must be mitigated by phasing in changes over time and implementing targeted carve outs (the elderly, low-income homeowners, small businesses, etc).

3) A revenue neutral replacement must balance predictable tax revenue that better matches the rising cost to provide public services.

4) “Bolt-on” incentives are fundamental to encourage the production of all types of housing.

5) Schools will benefit from returning education funding to local control and away from state mandates.

Any proposal too dogmatic without concessions to opposing sides is destined to fail, and I look forward to these ideas evolving with collaborative input from anyone interested in a genuinely brighter future for California.

Lastly, a key element of California’s fiscal challenges that this proposal does not address is wasteful spending and bureaucratic bloat. But there are only so many political battles a single proposal can attempt to win.

Proposition 13’s Origin Story

It’s no wonder that Californians freaked out about property taxes in the 1970s: When Prop 13 was passed in 1978, home prices were rising faster than even the bubbly days of the subprime mortgage boom.

By 1978, California had accumulated an almost $4 billion surplus thanks to ballooning property tax revenue and a strong economy. But without seeing services improve in kind, Californians begun to push for redistribution of those funds in the form of property tax relief.

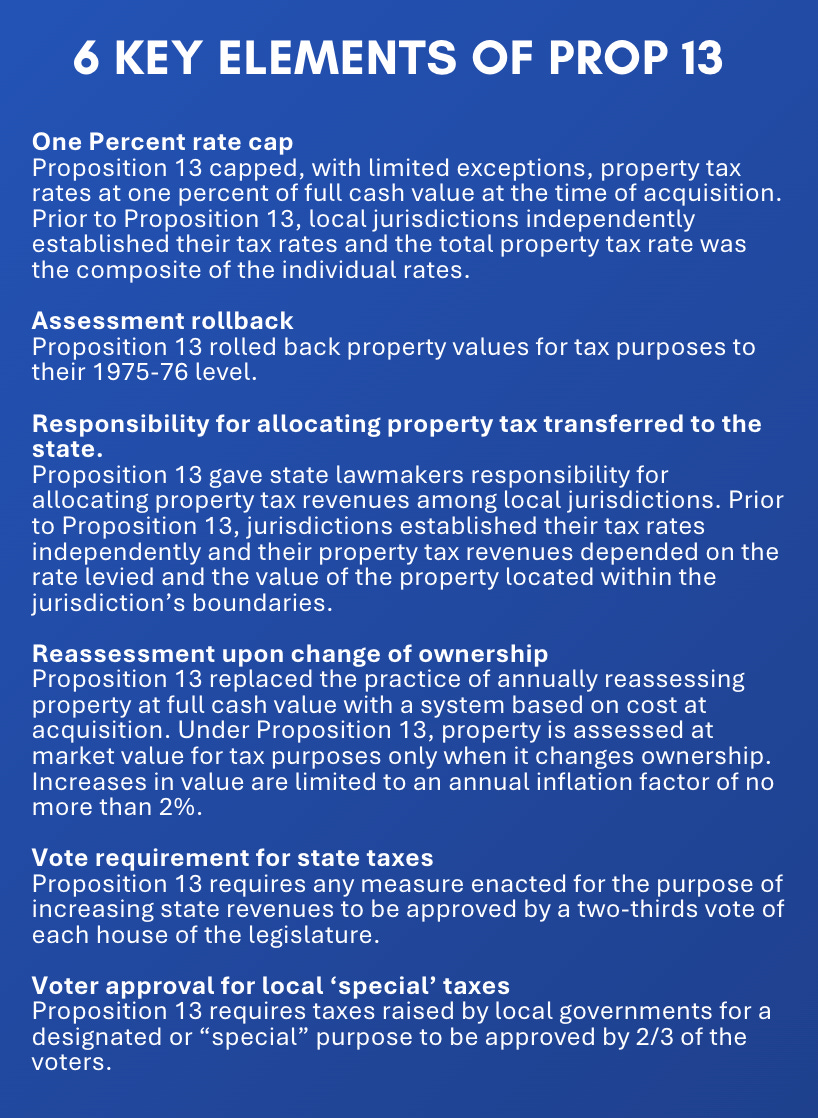

Led by populist tax reformer Howard Jarvis and funded in large part by real estate interests, Californians voted Prop 13 into law in 1978 by a wide 65-35 margin. The historic legislation, which many credit as kicking of a nationwide “taxpayer revolt,” included several key elements designed to ease the property tax burden on Californians:

The immediate $6.1 billion (53%) drop in property tax revenue blew a hole in the state’s finances for decades, but perhaps the most insidious element of Prop 13 was how deeply the designers woven it into the state’s constitution.

Now almost 50 years later, no one has been able to untangle it.

And as property values have risen steadily and significantly in California — far faster than the mere 2% that property taxes are allowed to rise — Prop 13 has created the infamous situation where neighbors owning roughly similar homes pay dramatically different property taxes.

Consider the following:

346 Felton Road in Menlo Park is 4-bedroom house with an estimated market value of around $5,000,000. Yet the property tax assessed value is just $835,000, with a 2024 property tax bill of $12,132.

Meanwhile a nearby home at 212 Felton Drive sold in 2023 for $5,200,000, and the new owners pay over $60,000 per year in property taxes, or five times more than the owners of a similarly valued home.

Same city services, but one owner pays $50,000 per year more in property tax. How can a system like this not breed resentment?

And while new homeowners — whether they move in from out of the country or around the corner — pay among the highest property taxes in the country, the effective property tax statewide is only 0.71%, ranking 35th in the country.

But hey, who doesn’t love low taxes?

Schools, for one.

Public schools are the number one recipient of property tax revenue in California. And this chronic under-funding has helped contribute to the state being ranked 40th in reading and math performance.

Roadblocks on the Way to Reform

Over the decades, hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent trying to reform Prop 13. Opponents have chipped away around the edges, but have ultimately failed to meaningfully change its impact on housing markets.

There are three broad challenges to reform, each of which my proposal addresses:

First, Prop 13 was designed specifically to thwart reform efforts, requiring any material change to Prop 13 be passed by two thirds of the legislature. The alternative would be a voter approved proposition, but both these options are high political mountains to climb.

Second, by keeping property taxes low on long-time residents and businesses, entrenched and powerful groups have united in their efforts to maintain the status quo.

This is one reason we see such a wide and unusual coalition of well-connected Californians opposing reform efforts: Propping up Prop 13 may be the state’s only true bi-partisan issue.

Finally, changing laws in California — especially ones supported by such powerful special interests — is incredibly costly.

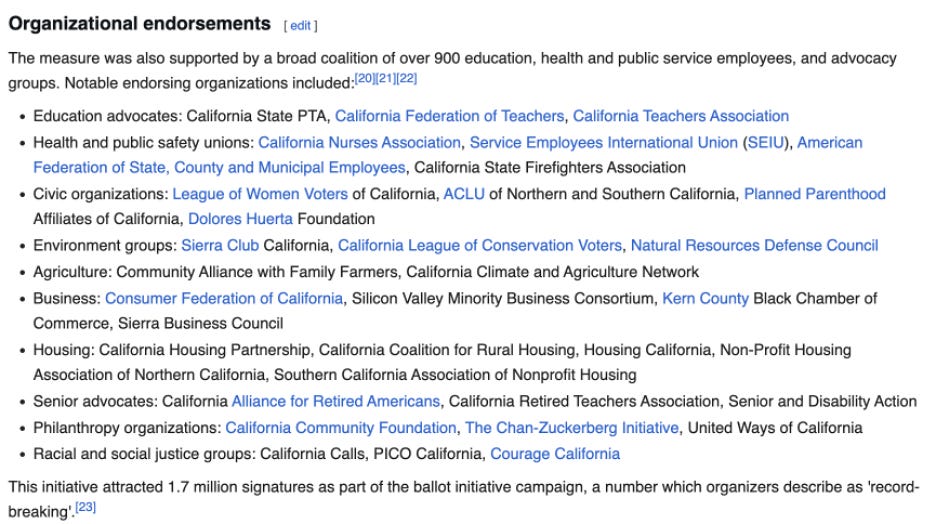

The closest thing to true reform was Prop 15 in the Covid-era election of 2020, which would have split the tax rolls into one regime for residential and one for commercial. The proposition failed narrowly, 52-48, and was estimated to have cost the two opposing sides almost $150 million.

Proponents argued that the change in tax rules would generate an estimated $6.5 – 11.5 billion in additional revenue, which could be allocated for public services like education. They hoped a carve-out for small property owners would resonate with Californians’ populist tendencies.

Prop 13 received broad support from teacher unions, major newspapers and high-profile US Senators like Bernie Sanders. The Chan Zuckerberg initiative was one of the top 3 funders of the almost $70 million raised to support the proposition.

This mirrors conversations I have had with certain wealthy Silicon Valley Californians who quietly support comprehensive Prop 13 reform because they understand the damage it has done to the state’s housing market.

Opponents to Prop 15 argued that much of the new tax burden would be shouldered by small businesses, since many retail leases push tax obligations onto the tenant. And that a split roll is just one step closer to full repeal of Prop 13.

The “No on Proposition 15” campaign raised more than $70 million from land developers and business leaders, including Blackstone Property Partners which donated $7 million.

Partially due to the pandemic-induced business climate of late 2020, Prop 15 narrowly lost 52-48, but demonstrated that a well-crafted split roll option had a chance to get approved.

However, at almost $150 million in combined costs and the tremendous political effort required to get broad support for such a measure, Prop 15 is also a cautionary tale for any serious attempts to repealing Prop 13.

Destined to Fail

Despite victories around the edges, efforts to dismantle the Prop 13 regime have largely failed because they have focused on changing who shoulders the property tax burden, and how they pay.

Repeating something I wrote at the outset:

Any serious attempt to fix the Prop 13 problem in California must at its core be a housing initiative. Because otherwise you’re just talking about juggling money from one pocket to another, hopelessly wading into unwinnable arguments about “fairness.”

Because despite the tremendous cost and effort advocates have gone to try and reform Prop 13, ultimately the debate devolved into a discussion about fairness.

Who should pay what, how, and where should the money go.

That’s a losing argument when trying to create a broad coalition to fight entrenched, powerful incumbents with little incentive to change the status quo.

True Prop 13 reform must be rooted in housing because poll after poll show that what Californians really care about is the cost of housing and other living expenses:

Of course, Prop 13 alone cannot be blamed for out-of-control housing costs and the abysmal process by which housing is built in California.

But when thrown into the legislative cauldron of laws designed to limit private control of land in the name of fairness (CEQA, restrictive zoning, inclusionary housing requirements, etc), Prop 13 anchors a regime that:

Artificially restricts the supply of homes for sale and developable land

Creates resentment and inequality in how homeowners share the burden of the costs of city services, and

Foments social division rooted in a deeply flawed property tax regime

So any serious attempt to fix the Prop 13 problem in California must attack the structural impediments erected over the years that disincentivize the construction of new housing.

How Prop 13 Impacts Housing Markets

When people talk about Prop 13 and the housing market, most of the focus is on the so-called the “lock-in” effect, where long-time homeowners’ low tax bills decrease mobility, crimping the supply of homes for sale.

A 2005 National Bureau of Economic Research study showed that owner tenure increased by about 10% across California from 1970 to 2000, largely attributed to Prop 13. The impact was many times stronger in high-cost coastal cities than lower cost inland areas.

But the residential lock-in effect alone understates Prop 13’s true impact on the housing market.

The “lock-in” of commercial property is perhaps more impactful on the housing market, because Prop 13’s low rate of annual increases allows owners of commercial property to more easily land bank, keeping developable land from becoming homes.

Take another example from my hometown of Menlo Park.

545 Middlefield is a trio of low rise office buildings totally around 80,000sqft sitting on 6-acres of land.

Based on recent sales which peg land value here at around $20 million per acre, let's call today's market value of 545 Middlefield around $120 million.

Which would equate to almost $1,500,000 in annual property taxes for a new owner.

Thanks to Prop 13, the current owner pays $200,000 per year.

It’s hard to know if this specific owner would sell if they were forced to pay market property taxes, but a 700% increase in property tax bills would shake loose some interesting sites. (Especially when coupled with capital gains incentives which I mention below.)

Opponents to meaningful Prop 13 reform suggest that it’s unfair to “force” property owners to sell because they can’t afford their taxes – a sentiment with which I mostly agree.

But do we really want California’s laws protecting owners of $100 million properties at the expense of more affordable homes for the everyone else?

Together with neighboring parcels along Middlefield Rd, there are almost 50 acres of low density, lightly used office buildings smashed between some of the wealthiest suburban neighborhoods in the country.

These low density properties front a main commuting artery with good access to freeways, and building here would have limited impact on nearby residential neighborhoods, other than some additional traffic.

Interestingly, a neighboring parcel to this site, previously owned by the USGS, just sold to a well-known Bay Area developer so we’ll learn about the real opportunities of the adjacent sites along this stretch.

In a region like the Bay Area with legitimate natural supply constraints, Prop 13 is a self-imposed limitation that jacks up the value of developable land, which is passed along to eventual renters and buyers.

Prop 13 also creates mismatches in the supply and demand for housing by suppressing property tax revenue from residential sources, which pushes local governments to focus on retail, office and other commercial development to fill municipal coffers.

It’s great that Amazon is building a new fulfillment center and creating 1,000 jobs, but if new housing units aren’t created at the same time, that’s 1,000 more people competing for the same number of housing units.

So while we like to cheer new commercial development and job creation, if building new housing isn’t just as easy, the growth so many cities crave will inevitably drive up housing costs. Just ask Nashville, Austin, Atlanta and countless other cities which used to have a reasonably balanced cost of living.

Serious property tax reform must address these imbalances to create the change in housing markets that Californians claim to want.

Key Goals of Reform

The Prop 13 tax regime is so intertwined into California’s economy, it’s an enormous challenge to craft a replacement that not only tackles the social, economic, political and housing-related challenges, but actually stands a chance of being approved by voters (and therefore not a giant waste of money and effort).

My proposal to repeal and replace Prop 13 is designed to achieve four specific goals:

1) Unlock housing supply and incentivize new development that will ease cost of living burdens that particularly burden middle and lower income Californians.

2) Protect at-risk homeowners and businesses by phasing in tax rate changes and carving out exceptions.

3) Stabilize and strengthen public revenue sources, returning more spending control to the local level (especially for schools).

4) Build a durable political coalition to focused on housing affordability, rather than “fairness.”

The Proposal Itself

The new property tax regime will have three key elements:

1) Lower Nominal Property Tax Rate, Regular Reassessments

The statewide property tax rate of 1.0% mandated by Prop 13 will be removed, and each county will set their own property tax level within certain state-mandated guardrails. This approach mirrors the property tax system in Arizona, which strikes a balance between low nominal rates and taxes set at the local level which are more responsive to local needs.

The current effective property tax rate in California is around 0.70%, so to keep the proposal revenue-neutral, the state will set a “corridor” of rates that are allowable (say 0.60% to 0.80%). Each county will choose a base rate within that band.

Counties and cities are then free to add on additional taxes as they see fit (parcel taxes, special assessments, etc), which maintains the existing administrative system to ease the burden of these changes on tax collectors.

Since there are California taxpayers who pay much less and much more than 0.70%, the impact of this change will be felt unequally throughout the state.

Long-term owners will bear the brunt of the increases - which is ultimately why Prop 13 reform is so hard to pass. To ease the burden on homeowners and businesses who will see their taxes go up, increases will be phased in over time on a sliding scale.

For example, a homeowner whose tax bill would rise by $10,000 per year would see around a $80 per month increase if phased in over 10 years.

The larger the increase, the longer the phase-in. This will be mirrored by owners who will see their property taxes go down, to maintain stable tax revenues during the transition.

Reassessments will happen every five years, with limits on annual increases that are less restrictive than Prop 13’s two percent annual increase.

Arizona, for example, sets limits annual increases to 5%, which means tax assessments more closely track property values and help prevent tax revenue from getting out of line with rising costs of delivering public services.

Lastly, the state will set aside a fund for certain counties where property tax revenues fall short spending required to deliver public services, especially education.

Lower income cities have historically been less successful in getting voter-approved parcel taxes passed than higher income cities, which exacerbates the funding available for schools in wealthy vs low-income districts.

In other words, the state fund will act as a safety net for cities with meaningful shortfalls, rather than the piggybank from which a majority of funding is shaken loose.

2. Circuit Breakers and other Protections

The bogeyman of Prop 13 reform is that removing property tax caps will “kick grandma out of her house.”

Since the intent of this proposal is a viable replacement of Prop 13, we address this common pushback head-on.

To address the very real risk that certain homeowners and businesses would be so negatively impacted as to be forced to move or shutter, we will provide circuit breakers and exceptions for certain situations.

For example, increases in property taxes on low-income households and certain seniors will be capped, phased in even more slowly, and in certain more extreme situations exempted completely.

Small businesses will receive similar protections if the passthrough of property tax costs via commercial leases would endanger their viability.

The risk here is that special interests chew away at the actual reform, so I expect this to be among the most complex and contentious portions of the proposal. But without these circuit breakers, the proposal would have no chance of seeing the light of the ballot box.

3) Tax Reform to Stimulate the Construction of all Types of Housing

Easing the stranglehold on new housing production can only happen if we free up more land to develop, incentivize cities to approve new housing, and make it cheaper and easier for builders to build it.

And since the real estate industry is one of the chief opponents of Prop 13 reform, including carrots for property owners and developers will be important in gaining support for the new rules.

Five key tax-related housing incentives to include are:

100% of capital gains on the sale of a primary residence is exempt from state income tax.

Currently, California conforms to IRS rules that exempt the first $250,000 for single filers and $500,000 for joint filers of capital gains on the sale of a primary residence. But many Californians would generate far more than that in capital gains liability by selling their long-held primary residence.

This creates a strong financial incentive to stay put and when coupled with a low property tax bill, reinforces the “lock-in” effect.

By lowering the tax burden on long-time homeowners, many of whom own homes that no longer meet their needs, we can free up supply for younger families and new arrivals.

Reduced state capital gains tax and tax rebates for commercial property owners whose land becomes housing.

This incentive directly targets owners of properties like 545 Middlefield mentioned above, whose underdeveloped properties could be turned into hundreds of housing units.

Higher annual property taxes and more favorable tax treatment on sale strikes a balance of changing the incentives to shake loose development sites, without being too heavy handed and “forcing” owners to sell because they can’t afford their property taxes.

1031 exchange laws already exist for owners who want to trade into new investments, but a minimally taxed clean sale could be preferred to holding a long-owned, low-taxed property (in inheritance situations, for example).

Equalize tax treatment on the development of for sale housing relative to rental housing.

For-sale housing is taxed more severely than building rental housing, a quirk in the tax code now getting more attention for its negative impact on new home construction.

While the larger impact is federal capital gains tax, California should support for-sale home building by waiving or reducing the tax it charges home builders.

Because fewer condos and starter homes are being built, first time homebuyers are renting for longer, soaking up the limited supply of rental housing. Lower taxes will allow builders to sell for less and make a profit, which will push more renters into homeownership.

Another way to make housing cheaper to build is setting the property tax basis at a developer’s building cost rather than market value, including allowing this lower basis to transfer to a new owner for a set period of time.

4) School bonds for new housing units.

The State will issue an education bond with funds awarded to districts where housing is approved and built.

As it stands today, property taxes generated by new development are netted out from education funds provided by the sate, further lowering the incentives for cities to be supportive of new housing projects.

5) Expand the California Welfare Exemption to all property owners willing to voluntarily rent at a discount to low-income tenants.

Currently limited to qualified nonprofits, which gatekeep this strong incentive to expand naturally occurring affordable housing, the California Welfare Exemption grants a full or partial property tax exemption to owners electing to lease units at below market rates to low-income tenants.

Contrary to the narrative that landlords are greedy rent-seekers looking to extract every cent from their tenants, many property owners would love to rent to lower income tenants, especially public servants like teachers, social workers and police officers.

But they won’t do it at the risk of losing money each month on their rentals.

I know this because as part of a recent consulting engagement, I spoke directly to dozens of owners who said that if they could get a property tax rebate, they’d happily rent to (in this case) teachers at discounted rents.

But due to high property tax burden and ownership costs, landlords have little choice but to seek market rents to cover operating expenses, let alone make a profit.

While administratively challenging to implement, this change would immediately create hundreds (likely thousands) of more affordable housing units without displacement.

How to make it work

I have no illusions about the tremendous amount of work it would take to make this type of legislation a reality. I quick look at the coalition built to support the Prop 15, the 2020 split roll ballot initiative, and the $70 million spent in a losing effort tell the story:

But since the original drafters of Prop 13 enshrined it in the state constitution which requires a 2/3 legislative vote to change, a ballot measure is the only feasible path.

Which is why the effort must not be symbolic in nature – it’s too much money and effort to waste proving a point. That is why thoughtful circuit breakers, exceptions, tax breaks for real estate owners, and other concessions must be built into the proposal.

Anything too hard line will be a waste of time and a disservice to the importance of these efforts for the future of California.

Conclusion

Fixing California’s housing crisis means confronting the structural rot at its core: Prop 13.

Previous reform attempts have overlooked this foundational problem, distracted by debates over fairness, even as the state’s affordability crisis has deepened.

This proposal offers a politically viable, housing-first replacement to Prop 13 — one that protects the vulnerable, empowers local communities, and unlocks the supply California’s housing market so desperately needs.

Because without bold reform, the state’s future will belong only to those who bought in early — locking out all but the wealthiest still trying to build a life in the greatest state in the union.

This is one of the clearest breakdowns I’ve read on why a repeal-and-replace path for Prop 13 has to be housing-centered, not fairness-centered. Your Menlo Park example says it all,tax caps that once protected homeowners are now shielding underused land in some of the state’s most buildable corridors.

But here’s my question: What’s your take on how this reform would interact with CEQA and local planning commissions? Even with capital gains exemptions and school bond incentives, don’t we still run into years of delays unless parallel reforms streamline entitlement? Would love to hear your view on that bottleneck.