The Mortgage That Broke America

The Rise and Fall of Herb and Marion Sandler, unlikely scapegoats for the subprime bubble

Herbert and Marion Sandler didn’t set out to pop the housing bubble.

All the couple really wanted was their slice of the centuries-old tradition of American fortune-seekers heading west.

But during the wildest years of the subprime mortgage craze, a Frankenstein version of an innovative loan they had popularized became the worst mortgages ever written, during a time when the worst mortgages ever written were being written every day.

The Sandlers didn’t cause the subprime mortgage bubble, of course.

But they ended up featured in a now-censured Saturday Night Live skit as “people who should be shot,” thanks to their role in the crisis.

You really can’t understand just how out of control the housing market got in the mid-2000s without hearing the story of two children of immigrants who became self-made billionaires by giving homeowners the ability to choose their own mortgage payment.

Which in hindsight might not have been a good idea.

There’s never been a crazier year in structured finance than 2006.

And I should know – I was there.

I sat on a trading desk directly across from the guy who sold our company’s subprime mortgage bonds to insurance giant AIG (later bailed out by the US taxpayer).

I watched the head of structuring whisper to the three major rating agencies in a shell game where bundles of the worst loans ever written earned the same credit rating as bonds issued by the United States Treasury.

Those were wild times, where fortunes were made by Wall Street’s sleeziest sharps, silver spoon Newport Beach loan originators, and condohotel speculators in Avondale, Florida.

Las Vegas strippers even famously piled their tips into the frothy housing market, and certain New York Knicks players “stated” their income on loan applications that crossed my desk.

Before the house of cards famously collapsed, almost taking the global financial system down with it.

--

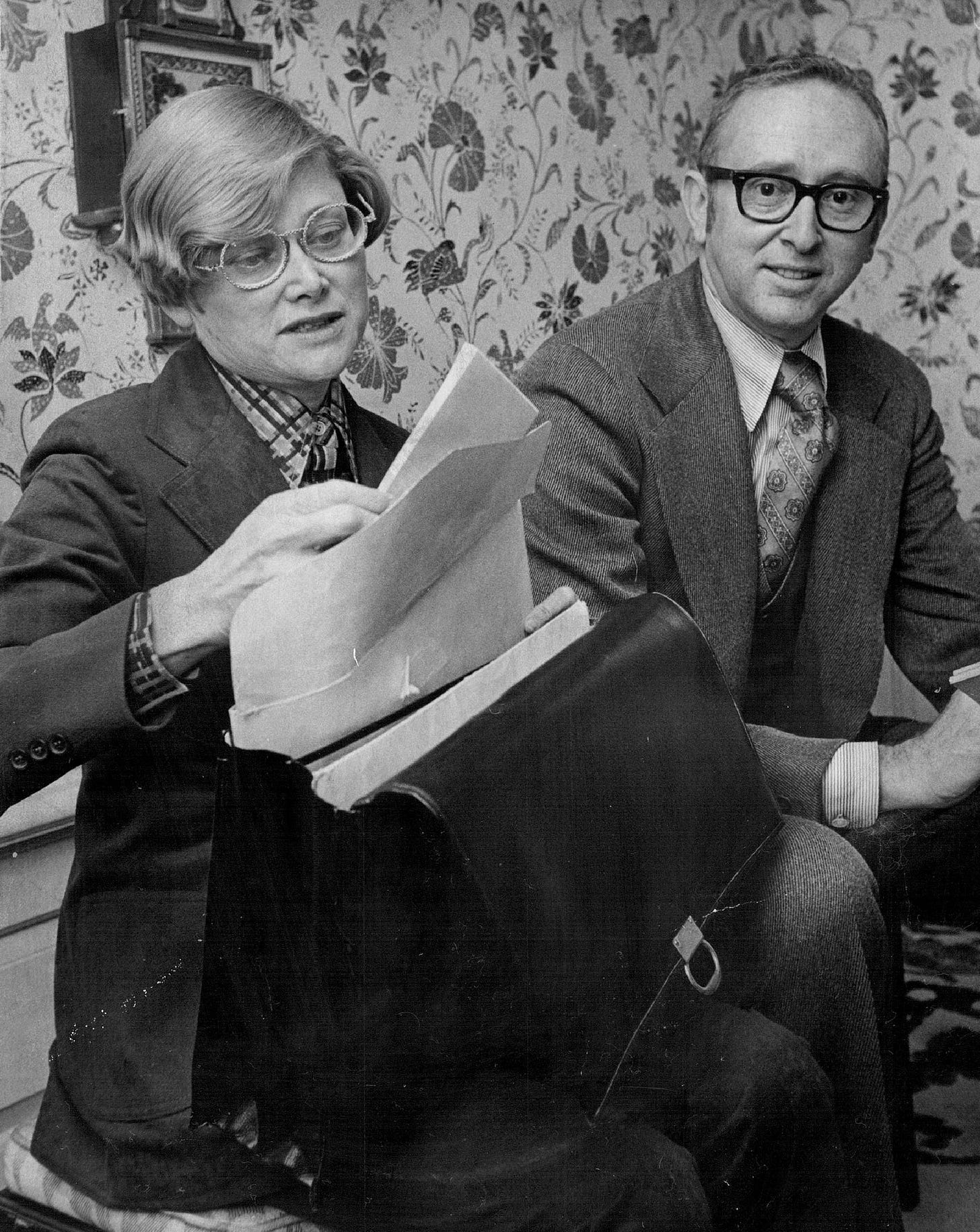

Herb and Marion met in New York, back when The Quarrymen hadn’t figured out yet that they were The Beatles.

Herb was a recent law grad from Columbia, Marion an NYU MBA. Both were the children of Jewish immigrants, two working class kids from New York who launched their careers in just the right place, at just the right time.

It’s said that Marion Sandler was the second non-clerical female employee ever hired on Wall Street. She started with Dominick and Dominick in 1955, one of Wall Street’s oldest financial services firms, before moving on to Oppenheimer and Company as an analyst for the savings and loan industry.

Imagine that scene for a moment. Imagine Marion Sandler, who personal accounts describe as a “force of nature, self-confident, smart,” surrounded by the Mad Men of Wall Street.

The two married in 1961 and two years later headed west in search of investment opportunities in the banking sector. Once settled in California they acquired Golden West Savings, an Oakland-based two-branch thrift, for $3.8 million in 1963.

The Sandlers renamed the bank World Savings and 43 years later sold for more than 6,800 times what they paid.

And for good reason:

Golden West has produced compound annual earnings-per-share growth of 20% over the last 35 years, a record that appears to be unmatched by any other financial firm, with the possible exception of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

— Forbes Magazine, May 2004

Just two years after the sale, thanks in part to defaults in the $120 billion portfolio of “option ARMs” on World Savings books at the time of the sale, their acquirer was forced to sell itself for less than 20% of its market capitalization at the time it bought World Savings from the Sandlers.

By that time, Bear Stearns was long gone, Lehman Brothers had just gone under, and the US Treasury Department was about to announce the single most important piece of financial legislation since the Great Depression.

But I get ahead of myself.

After taking the bank public in 1968, the Sandlers expanded into Colorado, and by 1975 had over 100 offices in the two states.

But these were challenging times to be running a bank.

During the stagflation era of the 1970s, fixed rate mortgages were depreciating assets.

Imagine a bank that wrote a bunch of home loans in 1973 at a 7% interest rate. When rates rose to 8% the following year, all those 7% loans weren’t looking so good. And worse yet in 1975 when rates rose to 9%.

Things got dire in the banking world as the decade ended with the energy crisis and oil shock of 1979, when rates leapt to over 15%.

Banking took action in 1981 by throwing the Sandlers some magic beans.

To help banks better manage their interest rate risk, regulators eased restrictions on adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), making them easier to write.

In some cases, the new federal rules overrode state laws that outright prohibited adjustable-rate loans.

Rising mortgage costs had become such a hot topic that consumer protection advocate Ralph Nader took up the cause, opposing the new regulations. Nader argued that consumers would be on the hook for the inevitable rise in interest rates.

1981 was the high watermark for mortgage rates, as well the end of Nader’s career as an interest rate speculator.

The Sandlers and World Savings leaned into the looser regulations, introducing their innovative “Pick-a-payment” loan in the early 1980s.

The Pick-a-payment was aimed at borrowers with inconsistent income like salespeople and the self-employed, offering a menu of payment options to ease the pressure of a single payment amount every month.

The bank’s strict underwriting practices drove stellar performance of these flexible loan along with the rest of their adjustable-rate mortgages, which helped the Sandlers skirt the 1980s Savings and Loan Crisis where thousands of banks went bust.

In the wake of the crisis, World Savings aggressively expanded its nationwide presence by gobbling up struggling banks up and down the East Coast.

By 1995, the Sandlers’ little thrift was the third largest mortgage lender in the country.

As the banking system healed from the S&L Crisis, Wall Street firms were leveraging the computing revolution and that new-fangled “Internet” thing to repurpose home loans into structured financial products.

Financial service lobbyists pushed to further loosen regulations, and booked a huge win in 1999 when Congress passed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA).

The new law repealed key parts of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, Depression-era rules which among other things had put up a wall between retail and investment banking activities.

The GLBA tore down that wall, allowing investment banks like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns to more easily open retail-facing operations (for example, buying home mortgages). Likewise, traditionally conservative retail banks like JP Morgan and Wells Fargo could more easily invest in exotic, highly leveraged mortgage-backed securities.

This toxic brew of main street money and Wall Street alchemy created intense competition for making and buying loans during the early 2000s.

Mortgage investors were making piles of money packaging and reselling loans, and to entice originators to sell them even more, drew up guidelines requiring less and less documentation from borrowers. As credit score minimums dropped and loan-to-value (LTV) maximums rose, market forces and lax regulations created a death spiral of irresponsible lending.

Adding gasoline to the fire, globalization was generating excess savings in developing economies like China.

After being admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001, China’s foreign exchange reserves rose from $212 billion to over $1.5 trillion in 2007, an more than 700% increase in six years.

And all that cash needed a home.

By 2006 when the housing market peaked, China was by far the largest foreign holder of government backed US mortgage bonds.

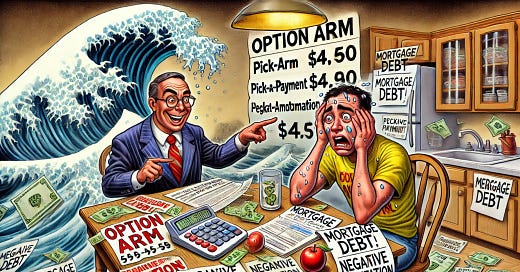

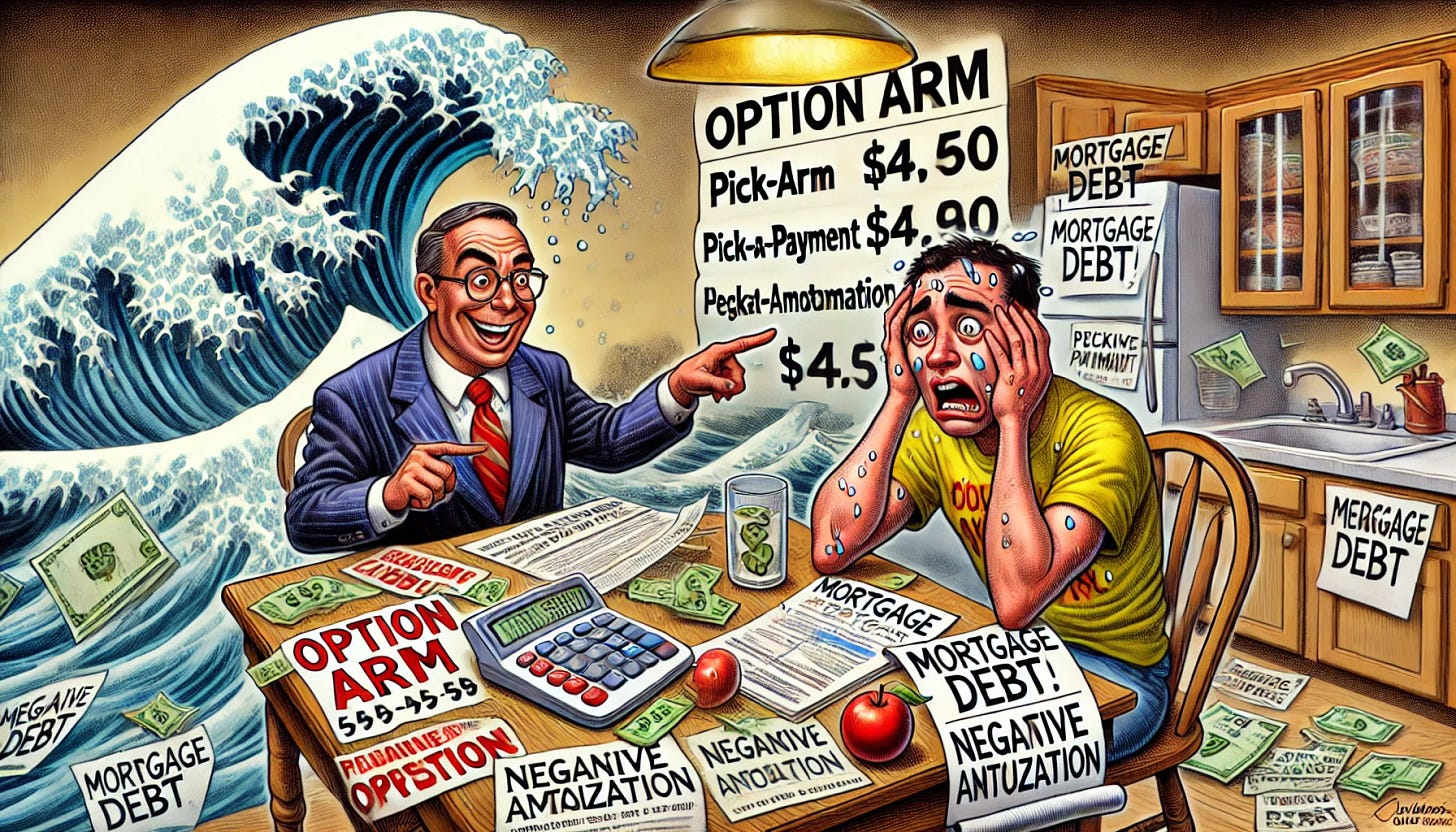

“Subprime” got all the headlines during and after the housing bubble, but no loan was more abused by lenders and speculators alike than the bastardized version of the Sandler’s Pick-a-payment: The Option ARM.

Which worked like this:

Unlike standard adjustable-rate mortgages with an initial teaser rate period before payments became fixed, Option ARMs gave borrowers the choice of four payment options each month:

1) Minimum Payment Option: Borrowers could make a very low payment, often less than even the interest due that month. This would result in “negative amortization,” where the difference between their payment and the interest due would be added to the loan balance.

2) Interest-Only Payment: Borrowers paid only the interest portion of their loan, usually available for 1-5 years before fully amortizing payments (ie, interest + principal) were required.

3) Fully Amortizing Payment: Borrowers made the full principal plus interest payment every month.

4) Accelerated Payment: Borrowers paid down extra principal each month to more quickly pay off their loan.

Short on cash one month? Make the minimum payment. Windfall another? Hack away at that principal.

These were useful loans for borrowers with inconsistent income streams.

And they were jet fuel for risk-hungry speculators.

I’ve never seen a quote that so perfectly captures the zeitgeist of the subprime boom, the complete disregard for anything resembling responsible lending, than what Countrywide Chief Angelo Mozillo said in 2003 at the Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Policy.

One of the more obvious resolutions to the “Money Gap” is the elimination of downpayment requirements for low-income and minority borrowers. Current down payments of 10% or less add absolutely no value to the quality of the loan. It is the willingness [credit history] and the ability of the borrower to make monthly payments that are the determinants of loan quality.

From my point of view, if 80% of the subprime borrowers are managing to make ends meet and make the mortgage payments on time, then, shouldn‘t we as a Nation, be justifiably proud that we are dramatically increasing homeownership opportunities for those who have been traditionally left behind.

From my seat on the mortgage desk, I saw exactly which investors were buying which loans. Option ARMs started trickling across the desk around 2004, and by 2006 they seemed as prevalent as subprime.

Subprime was a bigger market overall, but the investors buying Option ARMs had the lowest underwriting standards on the Street.

None of the biggest buyers of Option ARMs in 2006 survived:

- Bear Stearns (bought by JP Morgan Chase in March 2008)

- Countrywide (bought by Bank of America in July 2008)

- Washington Mutual (bought by JP Morgan Chase in September 2008)

- IndyMac (declared bankruptcy in July 2008)

- Wachovia (bought by Wells Fargo in December 2008)

But even in 2006 as home prices stopped going up, investors like Bear Stearns were pumping their new toy:

The rapid increase in securitization of option ARMs and the favorable performance characteristics of these securities make them an attractive investment opportunity in today’s market, according to analysts at Bear Stearns.

But the “favorable performance” of Option ARMs wouldn’t last.

By 2009, serious delinquencies (60+ days past due, in foreclosure, or held-for-sale) for Option ARMs had risen markedly. For instance, delinquencies increased to 40.4% from 33.3% for 2005 securities, to 47.3% from 38.6% for 2006 securities, and to 41.3% from 30.4% for 2007 securities.

In other words, almost half of all Option ARMs originated in the year that the Sandlers sold World Savings to Wachovia went belly up.

And recall that the most senior of these bonds, which were supposedly the highest quality, received AAA ratings — the same credit rating as US Treasury bonds — from Moodys, Standard and Poors and Fitch.

According to one report, 65% of Option ARM borrowers chose the minimum, negative amortization monthly payment. Which meant that as much as $487 billion of the $750 billion in Option ARMs originated between 2004 and 2007 were growing every month rather than being paid down.

Right when home price appreciation was grinding to a halt.

And right when the Sandlers were inking their billionaire-making deal.

In an effort to expand into high-cost states like California and Florida, Wachovia purchased World Savings for $26 billion in May 2006. The Sandlers personally took home $2.6 billion, which they immediately plowed into their philanthropic endeavors.

The sale included a $120 billion loan portfolio, including $90 billion of Option ARMs, whose performance was a key reason Wachovia was forced to sell itself just two years later to Wells Fargo.

Following the numbers, in 2006 Wachovia was worth $90 billion and paid $26 billion for World Savings.

In 2008, Wells Fargo paid $15 billion for Wachovia, just a bit more than half of what the bank had paid for World Savings only two years before.

What happened after 2006 has been reported on ad nauseam, but here’s how it went down from my front row seat:

Home prices stopped going up in 2006. The American home buying public just tapped out, and even Option ARMs couldn’t keep the train of fraud and abuse rolling.

As appreciation slowed, speculative borrowers could no longer flip their investment properties or refinance into the next teaser rate loan.

So they started not being able to make their payments.

Defaults spiked in late 2006, spooking mortgage investors that perhaps the music had stopped (it had). Which sparked a mad rush to unload the worst loans onto the greatest fools (this was the year that, ahem, the Sandlers sold World Savings).

As defaults rose in 2007, losses ripped through financial markets as investors scrambled to determine which of their trading partners were most exposed. But thanks to the opaque web of derivatives tied ultimately back to the failing mortgages, it was impossible to know which firms were left holding the bag.

This uncertainty drove fears over “counterparty risk,” and previously robust financial institutions became toxic.

This is what happened to Lehman Brothers in the fall of 2008.

Lehman wasn’t actually among the worst offenders during the subprime mania, but trading partners abandoned the storied firm as rumors of its insolvency rippled across Manhattan’s Bloomberg terminals.

The crisis crescendoed in 2008, first in the spring when Bear Stearns collapsed, and later in the fall with the failure of Lehman and the government bailout of insurance giant and avid subprime bond buyer AIG.

By then, I had moved on from the trading desk to a reporting beat.

I woke up each day and wrote about the biggest stories in finance, and my biggest challenge was choosing which of the colossal dramas to cover.

It was around this time that Herb and Marion Sandler reenter the story, thanks to, of all places, Saturday Night Live.

In October 2008, SNL aired their infamous “Bailout Sketch,” haranguing various players in the subprime saga, including billionaire mega-donor George Soros.

The sketch even painted then-President Bush in a positive light, but it dragged a little-known couple, Herb and Marion Sandler, as “people who should be shot.”

The clip was pulled offline the following Monday, edited, then reposted with “The Sandlers’ ” cameo missing from the version that can now be found online.

And later that month, the federal government announced the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP.

TARP was the biggest slush fund ever created, and was eventually used to bail out the Big Three US automakers, effectively marking the end of the crisis. Washington’s willingness to finance the bubble’s most toxic assets sent the message that Uncle Sam wasn’t going to let subprime take down the global financial system.

The impact of what was popularly viewed as a Wall Street bailout is still being felt today, as recently as last November (read my take on the direct line between TARP and the election(s) of Donald Trump).

For their part, the Sandlers vehemently defended their innocence in the subprime debacle, including against former employees who claimed the bank’s owners were complicit in reckless lending.

Paul Bishop, a mortgage salesman at World Savings San Francisco Loan Origination Center, told 60 Minutes in 2009 that he raised concerns to the Sandlers during the bubble:

We're breaking the law, okay? We're breaking the law. You know we're breaking the law. I know we're breaking the law. What the hell do you think is going on here? You know, you're granting too many people loans who simply can't qualify.”

'We're sitting on an Enron.' This is…bigger than Enron. I mean, we're doing four billion a month in loans. If housing drops, housing value drops, people start to default, you know? This is a nightmare. These people will not survive it.

Herb Sandler declined to be interviewed by 60 Minutes, but sent two letters (here and here) defending and his bank’s reputation and calling into question the whistleblower Bishop’s integrity.

We may never know if the Sandlers saw it coming, or if their sale to Wachovia was more luck than smarts.

But we do know that the same year that home prices peaked, as Wall Street was binging on the very loan product that catapulted World Savings to the top of the mortgage world, Herb and Marion Sandler cashed out as billionaires.

Not a bad trade.